India’s MedicalDevice Industry: A Quiet Revolution

Make-in-India’s growth catalyst, which the country’s policymakers are desperately seeking, could emerge not from Chennai or Pune or Gurugram, but from Surat, the city that put India on the global diamond-industry map. The mercurial success of India’s domestic stent-making industry, led by Surat-based Sahajanand Medical Technologies, has shown the way.

By Aanand Pandey, Editor, DMI

September is one of the warmest, sunniest months in San Diego, a scenic beach town in Southern California, US. Popularly called ‘America’s Finest City’ due to its year-round balmy weather, lately San Diego has been attracting people who have more than sun and sand on mind. These are the people who work at the cutting edge of one of the most important vocations in the world – healthcare research and development. For a good reason. Fuelled by state support, local organizations’ astute business sense and an abundance of university-nurtured talent, San Diego has emerged as a major healthcare research hub. A Biocom Life Sciences Associations report noted that healthcare activity accounted for $33.6 billion in total economic impact in San Diego in 2016. San Diego County houses more than 1,225 life-sciences establishments, including the pharma giants Eli Lilly, Pfizer, and GlaxoSmithKline, and more than 86 independent and university-affiliated medical research institutes.

It’d be hard to imagine that an event that unfolded in San Diego this September could unlock the fortunes of a company based 14,000 kilometre away in Surat, India, and possibly turn around the fate of India’s nascent medical devices industry. But that seems to be the case from all accounts.

This year, from September 22 to 25, the city of San Diego hosted the 30th anniversary of Transcatheter Cardiovascular Therapeutics (TCT), one of the most prestigious annual congregations of world’s top cardiovascular healthcare professionals.

A 12-minute presentation made on the second day of the conference grabbed the headlines of India’s major newspapers the next day. The presentation, given by Patrick Serruys, a professor of cardiology at London’s National Heart and Lung Institute of Imperial College, revealed the results of a large-scale randomised clinical trial of DES (Drug-Eluting Stents) held in Europe.

Presciently titled TALENT, the study compared the quality and performance an Indian-made stent with the best-in-league Xience stent of Abbott Laboratories. As per the study, Supraflex sirolimus-eluting stent (SES) made by Surat, India-based medical devices company Sahajanand Medical Technologies, was clinically at par with Xience, widely regarded as the global standard for drug eluting stents. Not only that, Supraflex’s success rate of 97.6 percent was comparable or even superior to other leading DES (Drug-Eluting Stents) including Orsiro, Resolute, and the Chinese contender Firehawk pitted against Xience in similar studies, the presentation said.

Any sector observer will tell you that these findings could have a far-reaching impact on the global medical devices industry, a large part of which is driven by the field of cardiovascular care.

Prof. Serruys, also the study chair, pointed it out during the presentation. “The study results have important economic implications in countries with capped stent prices such as India, and in some European countries with competitive pricing and different models of healthcare cost savings,” he said. It would be pertinent to note that the study was sponsored by Sahajanand Medical Technologies. It is an accepted and a well-recognized practice for healthcare companies to sponsor randomised clinical trials to test the efficacy of their products.

The matter of the heart

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death globally. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), cardiovascular disease accounts for about 40 percent of all the deaths in the U.S. The figure is even higher at 45 percent for Europe, says WHO. Developing countries are catching up fast. A recent WHO study said that one in five adults in China has a cardiovascular disease, and the number of CVD events are predicted to increase by half by 2030.

Along with population size, this is an area where India is hot on China’s trail. Lancet, a prestigious peer-reviewed medical journal, published a report in September on the prevalence of CVD in India. The study, funded by Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, presented a detailed analysis of how the patterns of cardiovascular diseases and major risk factors have changed across the India’s states between 1990 and 2016. The findings were alarming. Overall, deaths from CVD almost doubled, from 15.1 percent of the total population in 1990 to a high 28.1 percent in 2016 and the loss in productivity, measured by a parameter known as Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALY) had more than doubled from 6.9 percent to 15.2 percent from 1990 to 2016.

In short, a potent combination of factors such as changing lifestyles, growing expectations and anxieties fuelled by the information explosion of the internet era, the large-scale migration of people to polluted, noisy urban centres, and genetic predisposition has made CVD a major killer and disabler in developing economies such as India and China. Healthcare companies, global and local, old and new, are vying to provide treatment to the fast-growing number of CVD sufferers.

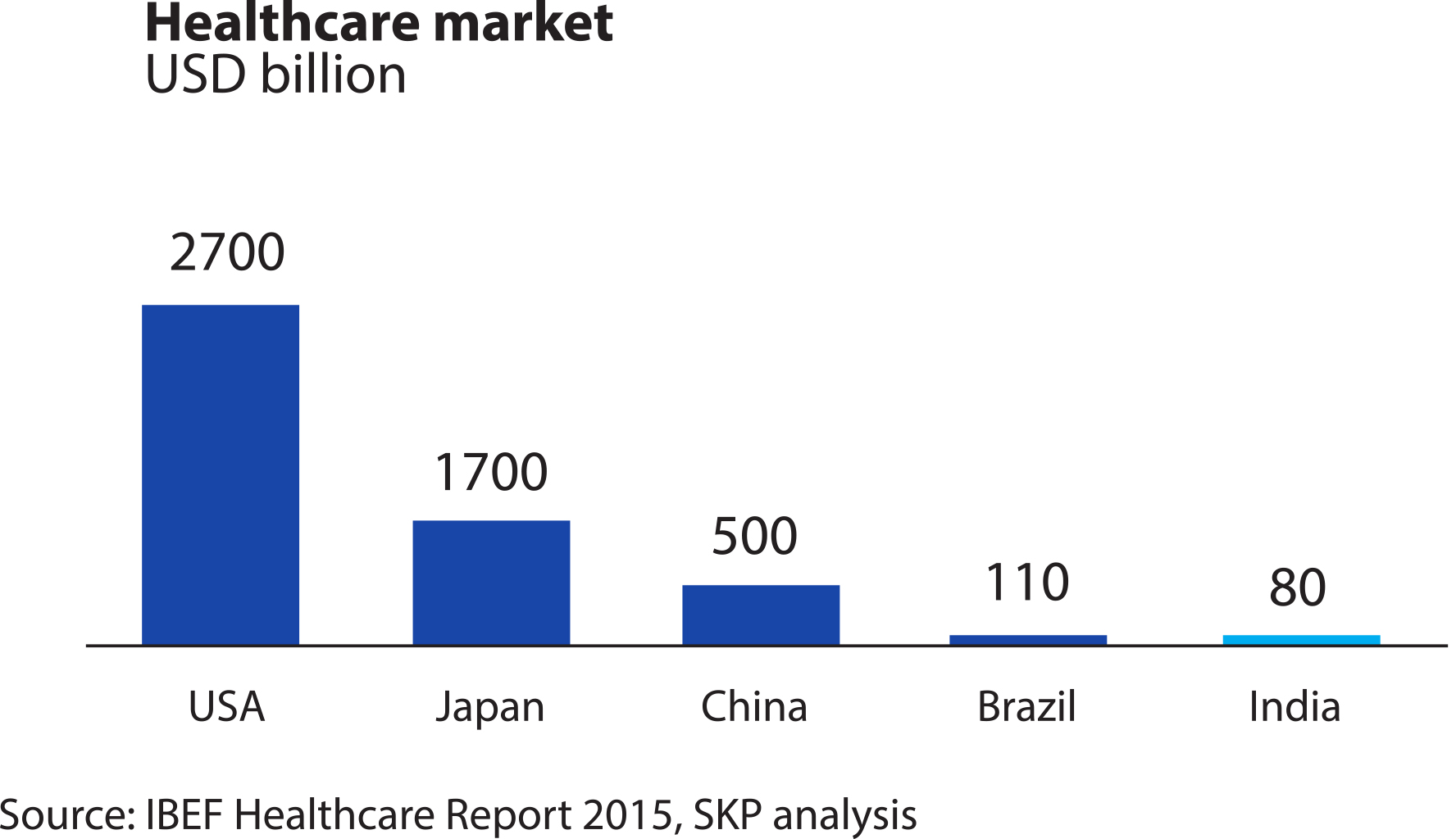

The field of CVD care is a huge, complex ecosystem, populated by innumerable healthcare delivery systems, therapeutic drugs, and monitoring, diagnostic and interventional medical devices. A recent Research and Markets report put the global market for cardiovascular devices at nearly $42.4 billion in 2017 which will reach an expected $59.1 billion by 2022. The sector is dominated by American and European companies backed by a robust legacy of research and development. Naturally, the home-grown companies of India and China and other developing economies play second fiddle. However, a fast-evolving field of CVD care – the use of intracoronary stents – has opened a window of opportunity for the greenhorns.

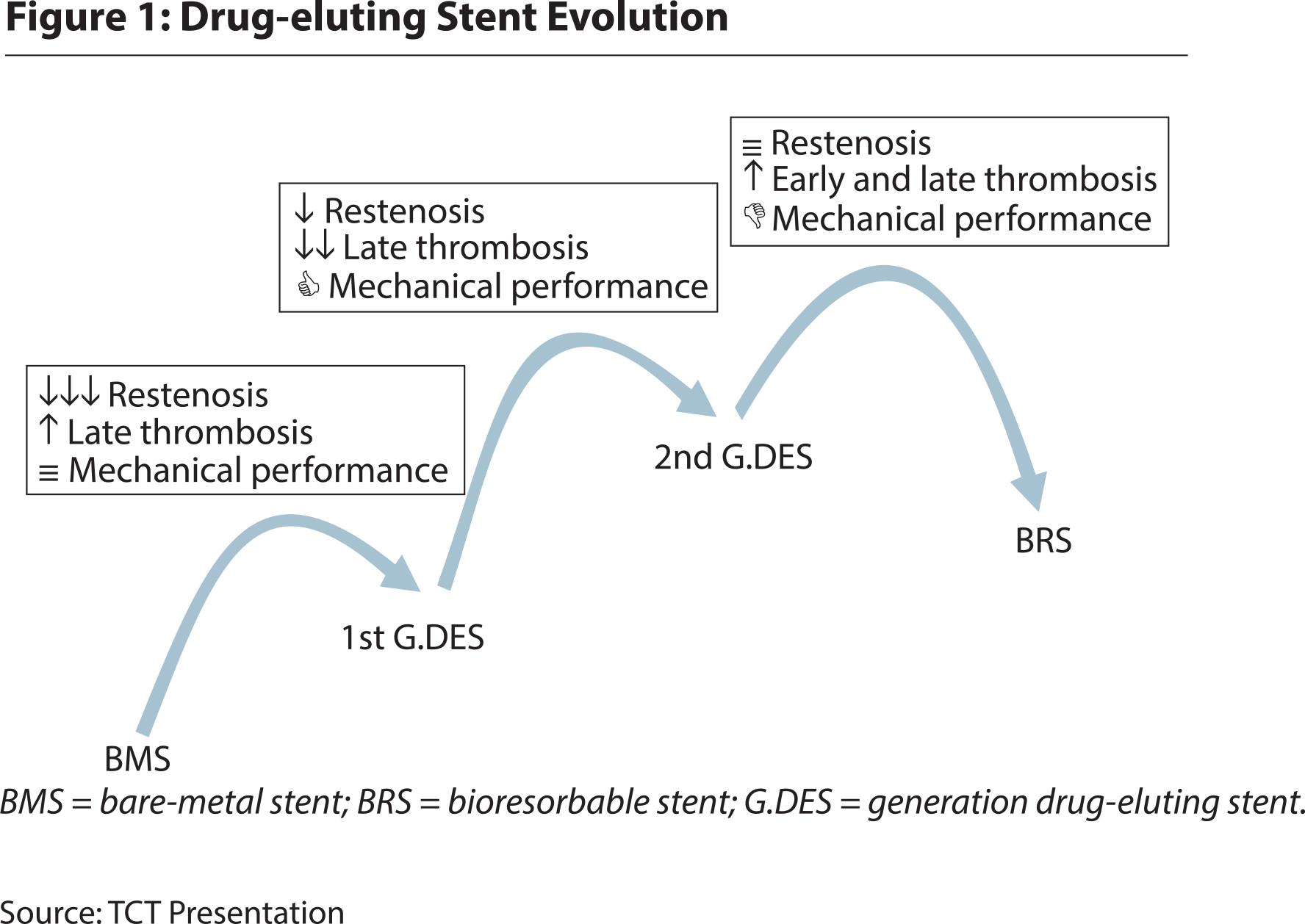

The use of stents is a relatively new phenomenon. According to The New England Journal of Medicine, the first intracoronary stents were successfully deployed in the late 1980s – as scaffolds to keep the arteries open after angioplasty, a medical procedure done to widen narrowed or obstructed arteries or veins. Doctors soon realized that stents helped reduce post-angioplasty complications. By the turn of the 21st century, nearly 85 percent of all coronary intervention procedures used stents. However, the early class of stents, now categorised as bare metal stents (BMS), often caused in-stent re-stenosis – re-blocking of artery due to scar tissue formation around stent – in 15-30 percent of cases. A new class of stents called drug-eluting stents, developed by Johnson and Johnson in the early-2000s, brought these incidences down to a safe level of under five percent. Drug-eluting stents (DES) are coated with a pharmacologic agent, a drug or a combination of drugs known to interfere with the process of re-stenosis.

Even though Johnson and Johnson closed down their coronary stent business in 2011 – citing a number of reasons that boiled to the fact that stents were fast becoming a commodity, the popularity of DES continued to grow. Today, DES dominate the $8.5-billion stent market. A new generation of DES technology, called BRS (Bio-resorbable stent), has been called the fourth revolution in interventional cardiology due to its potential advantages. As it does, success breeds competition, which it has in this case.

Let the stent wars begin

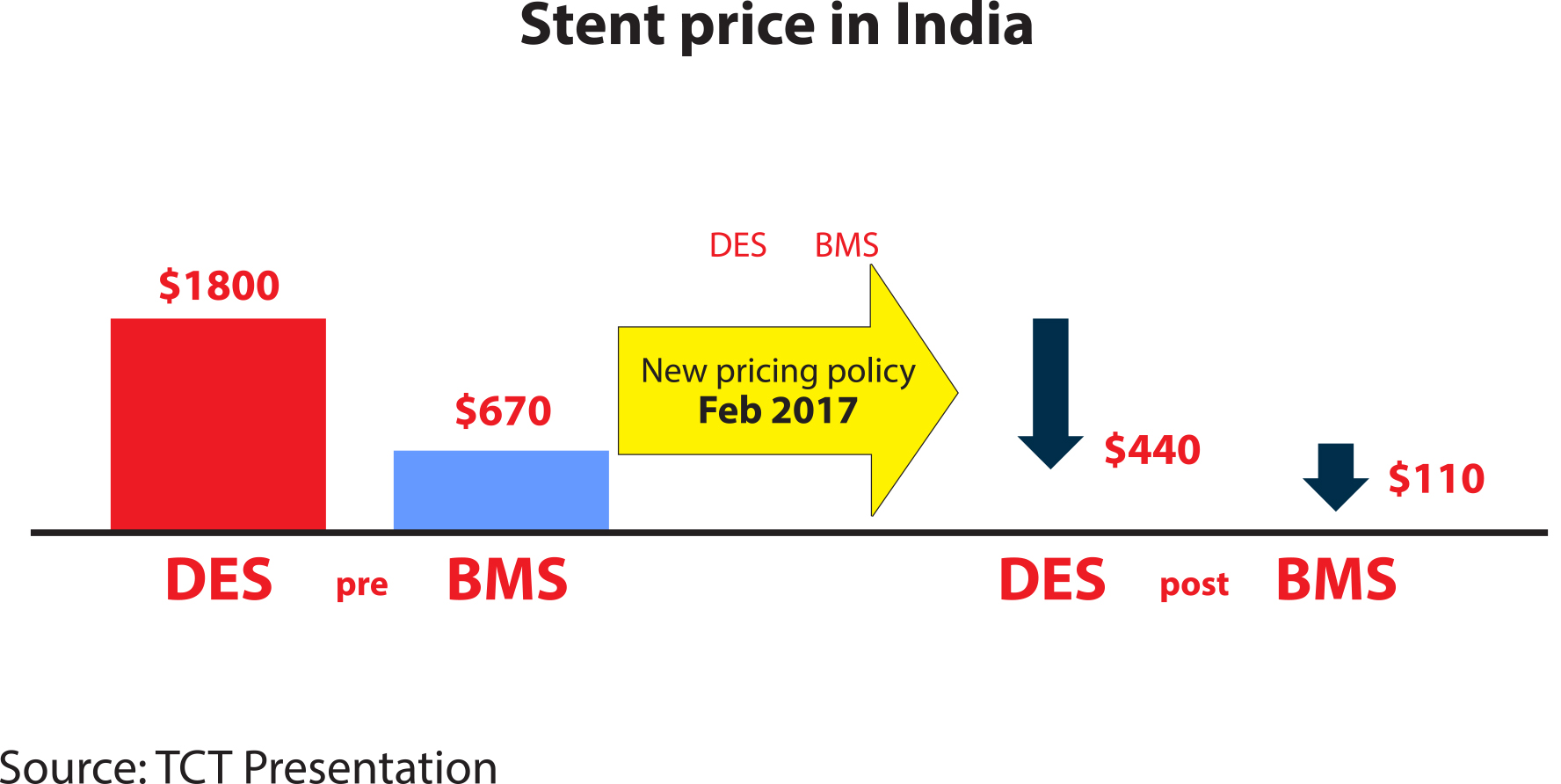

Johnson and Johnson had the right hunch about the future of stents. The fast and the furious innovations in stent technology have propelled the use of the device. According to the recent estimates, every year over 1.8 million stents are implanted in the US alone. The fast-growing market has attracted new players, forcing international companies to slash their prices. A Modern Healthcare article noted that prices of stents in the US have been dropping in recent years and in 2016, the average price hovered around $1,200. While a price point like that would be easily affordable in tightly regulated and neatly structured healthcare systems of the US or Europe, India’s opaque healthcare market, with its proclivity to create artificial scarcity and maximise short-term gains, made stents prohibitively expensive for the average patient. India’s National Pharmaceutical Pricing Authority (NPPA), the drug and devices pricing regulator, found out through an enquiry in 2016 that the maximum retail price of stents was marked 150 percent to 400 percent above their import price. It meant that, for example, a fourth generation DES with a landed import price of Rs 2 lakh ($2,900 in 2016’s average exchange rate) was out of reach of most of the patients.

However, a landmark decision taken by NPPA last year put a stop to such practices. On February 14, 2017, NPPA capped the price of DES at Rs 30,180, and further revised it downward to bring it under Rs 28,000 this February.

As expected, global sector experts and healthcare majors rose up in arms. Many leading stent makers threatened to pull out of the market, and the biggest of them all, Abbott Healthcare followed up – it withdrew two of its latest generation stents, including the premium Xience Alpine stent, from the Indian market.

Expressing his disapproval for the sweeping move, India’s renowned cardiologist and Medanta CMD Naresh Trehan told the news website Money Control that “The cap has led to a lack of stent innovation in the country. Patients from abroad have stopped coming as they feel we lack the latest in stent technology. We need a quick decision from the government to resolve this as we have started to lose ground.” Tim Worstall, a Forbes magazine columnist drew an analogy between India’s stent market and a housing market, and warned, “When governments have rent control to make housing nice and cheap then people stop building it,” alluding to a possibility that the price cap will hinder innovation in the segment and create a supply deficit of stents in India.

Turns out the healthcare-sector experts vastly underestimated the business instinct and tenacity of Indian entrepreneurs.

Who dares wins

Sahajanand Medical Technologies (SMT), the developer and maker of Supraflex DES, proven to be one among the best, is based in Surat, Gujarat. The company has its roots in the city’s diamond cutting and polishing (CPD) industry, which brings to India its largest share of exports ($29.4 billion in 2016). It’d be news to many that CPD exports is bigger than the much-celebrated exports of refined petroleum ($22.8 billion), pharma and automotive.

SMT’s Founder-Chairman, Dhirajlal Kotadia started the parent company, Sahajanand Technologies, in 1993 to cater to the Surat’s CPD industry with laser technology. Although the popular media, including India’s leading newspapers and a number of books written on the subject say that it was the use of laser technology that revolutionised Surat’s diamond cutting industry, it appears to be an abstraction because, one, Surat’s CPD industry had already taken off in the mid-80s, and two, until the year 2014, only 5 percent of Surat’s CPD units had installed laser-cutting machines, noted a report by Industrial Laser Solutions for Manufacturing, an industry magazine published during the same year.

What is clear, however, is that Sahajanand Technologies saw that its laser-cutting expertise could be put to good use in making stents during the early-2000s when the stent industry was taking shape in the US (the first-ever DES, Cypher, for the US market was approved in 2003), For SMT, it was a strategic foresight that has paid rich dividends.

As per media reports, SMT had gained around 11 percent of India’s $1,500-crore stent market till 2017. NPPA’s 2017 price-capping measure helped — as it did other manufacturers – to increase its share substantially. By September 2018, SMT’s share of the domestic stents market had grown to 22 percent, barely a few points away from the market leader Abbott Healthcare that has about 25 percent share, as per a Business Standard report. Besides India, SMT also exports its products to Italy, UK, Spain, Netherlands and over 60 other countries and enjoys around 5 percent share in the international stent market. During 2017-18, SMT’s estimated turnover was Rs 230 crore (source: ET), and enthused with the results of the TALENT study, SMT has set its sights on a turnover milestone of Rs 300 crore, a record high for any Indian medical device manufacturer.

SMT’s early positioning in the stent market and its success has attracted a number of domestic players to the sector, in many cases, literally so. Out of 20 leading domestic stent-makers, more than half are based in Surat or nearby hubs.

India’s Medical Device Industry: SMT Shows the Way

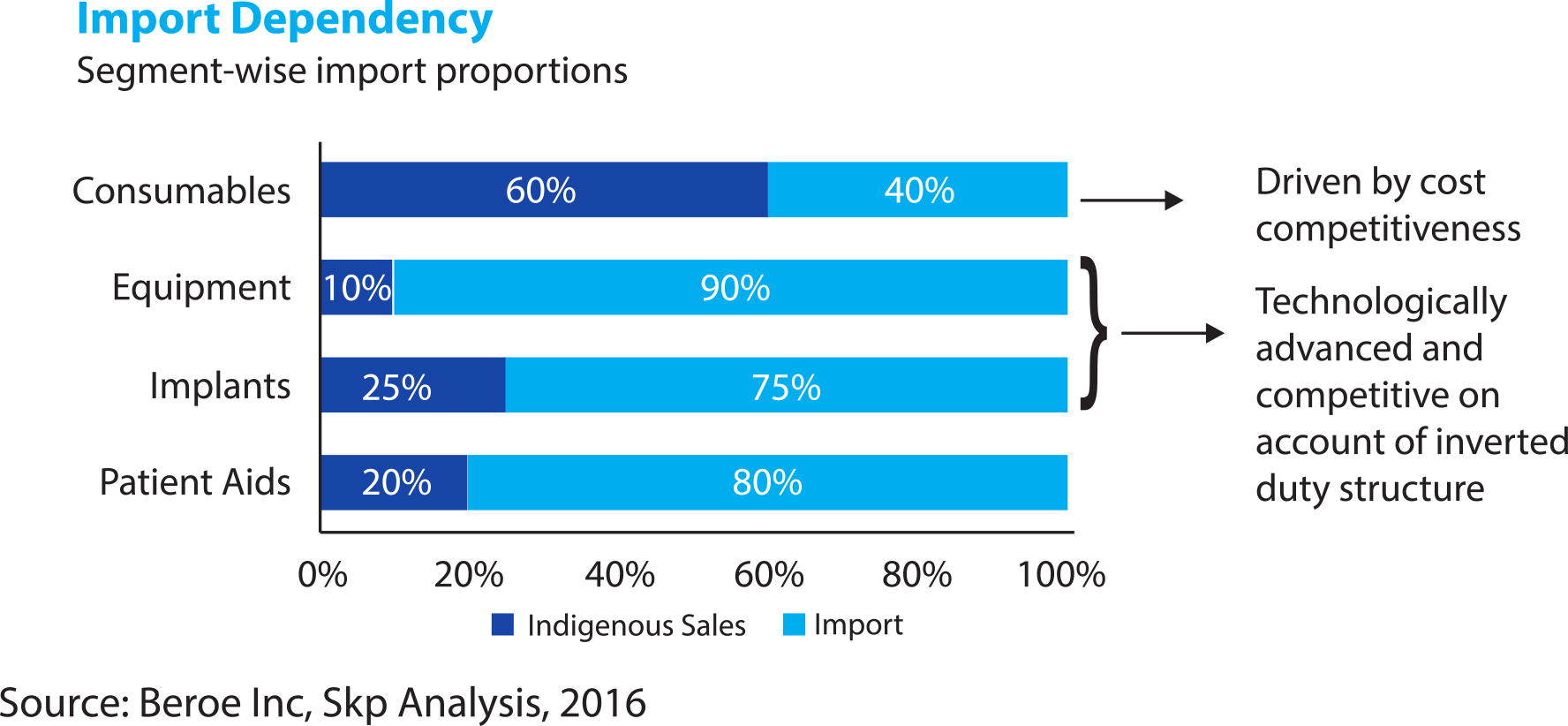

According to a Mumbai-based SKP Business Consulting’s March 2018 report on the sector, India’s $6-billion Medical Devices market is heavily dependent on exports, with about 75 percent of requirement met through imports. Segmented into equipments and instruments, consumables and disposables, implants, patient aids, and stents, the industry is highly fragmented with very few domestic companies (less than 10 percent) managing turnovers above Rs 50 crore.

Other sector reports also show that the Indian medical device market, despite its huge growth potential – it’s poised to grow to $50 billion by 2021 by some estimates – is largely underserved.

The domestic companies are constrained from two sides. At home, they struggle to find way amid intense competition from global players, opaque supply chains dictated by intermediaries and powerful healthcare establishments, and a lack of R&D legacy. Globally, they fight for crumbs in a market dominated by companies from the US, Europe and China.

The Indian government has come to the support of homegrown companies with encouraging policies and regulations. Mumbai-based consulting firm Nishith Desai and Associates points out in a recent report that in 2017, the government overhauled the regulatory framework for medical device, bringing it at par with international norms by introducing the concept of ‘risk-based’ regulation. “The regulatory licenses issued manufacture or sale of medical devices have been made perpetual in nature to cut down on unnecessary and time-consuming paper-work in a bid to increase ease of doing business in India. Foreign direct investment in medical device manufacturing sector is permitted without any prior approval from the government. The already robust intellectual property rights regime in India has been strengthened further by tweaking of rules for grant of patent and trade mark in the last two years.” Furthermore, the Indian Government has introduced various fiscal measures to promote research and development in the field. For example, the government has incentivized scientific research and development by providing weighted deduction for the expense incurred for the purpose. There is minimal or no import duty on certain medical devices.

In the international market, the share of India-made medical devices is miniscule. However, recent successes of the domestic stent-making companies, led by Surat-based SMT, provide a well-honed, winning playbook to the Indian players. Early sighting of new opportunities, competitive pricing strategy coupled with a laser-like focus on quality will help them take a bigger pie of the global market. Historically, the biggest hurdle for Indian companies has been the perception barrier, one that SMT has taken on successfully with the TALENT trial results, showing how the home-grown medical device manufacturers can compete fairly and squarely with the best in the world.

Indian stent market:

Main players

- Abbott Healthcare Pvt. Ltd.

- B. Braun Medical (India) Pvt. Ltd.

- Boston Scientific India Pvt. Ltd.

- India Medtronic Pvt. Ltd.

- MIV Therapeutics (India) Pvt. Ltd.

- Meril Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd.

- Relisys Medical Devices Ltd.

- Sahajanand Medical Technologies Pvt. Ltd.

- Opto Circuits (India) Ltd.

- Vascular Concepts Ltd.

- Envision Scientific

- Invent Bio-Med

Source: Journal of Industry, DMI